Peril in Three- Quarter Time

By Angela Camack

Once she could talk about it, when people asked how she'd coped with being shut up with him, she replied, "The music. It kept me sane."

Emily DeCarlo was a librarian at the New England Conservatory. library Trained in voice and piano, she was good enough to recognize that she would never be a professional musician. So, she moved into a career that involved her other love, working with people. She was good at her job. No, book, no article, no sheet of music remained unfound, no question unanswered when the library was Emily's dominion. Emily ruptured all the stereotypes about librarians. Kind, welcoming, very smart, her curvy little body, chestnut curls and huge green eyes didn't hurt.

The campus was a wonder for music lovers. It existed on a wave of music. Voices, violins, horns and guitars were heard on the grounds and inside the public spaces of the university, as if the making of music was inseparable from the rest of the musicians' lives. Emily was very happy with her job and her life, her little Boston apartment, her friends, and now her engagement to Charles, a psychologist who worked with children at Boston Medical Center.

But life likes to keep us unbalanced. Emily began losing her balance when she came across Grady, a maintenance worker at the Conservatory. Everything was innocent at first. Grady came to her one afternoon when she was at the reference desk. He had a question about a minor medical problem. Emily was glad to help, as the library encouraged employees to use the library. After that, he would stop by and chat if he was in the building, usually talking about what was happening at the Conservatory. He was a very tall man, broad but solid. His work gave him a lot of muscle. He was balding, with almost colorless hair, and a face weathered from outdoor work. He moved like he was unsure how his body would behave in small spaces.

He continued to drop by her desk. Once, when she was doing an evening shift, during the dinner lull, he shared that he loved music, but his family didn't have the money or motivation to pay for serious lessons. Working at the Conservatory was as close as he could get to what he loved. Why did his visits make her uncomfortable? He wasn’t the only person on campus she chatted with. If things became too close for comfort, she could tell him she was engaged. There was no problem there. But something about him tweaked Emily’s radar.

Then Grady's visits happened several times a week, often to discuss the same problem they'd solved before If she was taking a break or eating lunch alone around campus, he'd "happen" to find her. She had a hard time steering their conversation from personal issues. All events that made her uncomfortable, but nothing that she could complain about.

That is, until he found her by her car as she was leaving one day.

He was nervous and tense. “I know this great little bar in Allston that has live music. How would you like to come with me Friday night?" he asked. "If you're not sick of music after being around it all week."

"Grady, that sounds really good. Thanks, but I'm with my fiancé on weekend evenings."

His face tightened. "You’re engaged. When did this happen?"

"Two weeks ago."

"You didn't tell me." He glanced at her hands." I don't see a diamond."

"We don't like them. They cost so much, and so many of the people who mine them are treated so badly." She pointed to the pearl ring on her ring finger." This is what he gave me."

"I can't stand liars, Emily."

"I' m not lying! Why would I lie to you?"

"To blow me off. Because you won't date me!"

"Wouldn't saying 'no' be easier?"

Grady's face was a furious red and he was sweating." No! Because you bitches can't give up a chance to jerk a man around!"

Emily didn't bother answering, just got into her car. It took two tries to get her keys in the ignition. She pulled away. Looking in the rear-view mirror, she saw Grady was still there, still red faced and glowering. "This is not going to be easy," she thought. "The only question is how far he'll go."

Grady ignored her if work brought him to the library, but she felt his stare. He began asking her co-workers if she was really engaged. Emily went to security when notes saying 'Liar' or 'Slut' were tucked under het windshield wiper. Security said nothing could be proved but to keep track of the notes. Grady finally tipped his hand when a long, rambling letter accusing her of "thinking she was too good to date a man who works with his hands." appeared in her mailbox at home. Really frightened now, Emily went to the Dean of the library. Grady's handwriting was identified. The incident was documented, and he was told not to approach Emily again.

Emily knew it wasn't over. It happened one bitterly cold night as she was going to her car after an evening shift. She had trouble unlocking her car door; it was hard using her tube of lock defroster with gloved hands. This gave her assailant more time, She felt a rough cloth with a sickly-sweetish odor cover her face, held by a rough hand. Blackness surrounded her before she could react. She woke, not sure how much later, with a blinding headache, in her underwear on a strange bed.

She pulled a thin blanket around her and walked unsteadily to the door, not really surprised that it was locked. Knowing it was probably useless, she began to shout for help.

The door rattled and Grady entered "I thought you'd be awake by now." He tossed a hospital gown on the bed. "Here."

"Where are my clothes? My purse? My phone?" Emily croaked.

"You won't need them while you're my guest."

"I'm not your guest." Emily pulled the blanket more closely round herself and staggered to the bed. “What did you give me?" Grady smiled. "Just a little ether."

Emily shook her head. "You could have set us afire. No wonder I feel sick."

"I know, ether can do that. Do you want some ginger ale?"

"I want to go home!" Emily tried to make her voice sound rational. "Look, let me go now and it'll be all over. I won't tell anyone. We'll go on like it never happened."

Grady snorted. "Back to you treating me like crap? Like garbage? Like getting me in deep shit with my boss?"

"You got yourself in trouble!"

"No, you did!" Grady came close, shaking a finger in Emily's face. "With your fake smiles, and fake attention, you led me on! And how do you expect men to react to you, built like you are?"

"Well excuse me all to hell for forgetting to wear my work tits to the library!"

Grady stepped a few paces toward her, then stopped. Emily had forgotten how big he was, how used to using his hands and muscles, how much damage he could do.

She lowered her voice. "Look we can be reasonable. People expect me to be in certain places at certain times. The library knows I never just not come in. My car's still in the lot. Charles -"

Grady snorted. “Charles. You afraid to leave your big-time psychologist on the loose?”

“How did you know he’s a psychologist? Oh, from the snooping around you did.” Emily sighed and pulled the blanket even closer. The room was chilly. Freezing air seeped around the windows. “If you think Charlie makes a lot of money, think again. He works with traumatized children at Boston Childrens’ Hospital.”

“So, your Chad’s a do-gooder.”

“His name is Charles.”

“Aw, they’re all Chads. The ones with the fancy degrees, the titles. Why bother with a working stiff when you can have Charlie?”

“Because he’s the one I love, and he loves me.” She sat on the bed. “Look, this isn’t doing any good. Just let me go. I won’t tell anyone.”

“Like you kept my letter a big secret?”

“Why are you keeping me here?”

“:Somebody needs to teach you a lesson about what it’s like to be alone.” I’ll bring something to eat and then you’d better go to sleep” He locked the door and left.

Emily started to cry, tired, despairing tears. Then she took control of herself. Where was she? A small bedroom with a small dresser and a wardrobe. There was a bathroom with a shower stall. The room was shabby, with peeling paint and smelled close, moldy. There were no pictures, no ornaments on the dresser. The bathroom had chipped tiles and stains around the shower pan. The room felt like human habitation was an afterthought to whoever owned it. She went to the window. The window was frosted, and it was full dark, so she had no idea where she was. She tried to open the window, but it was stuck tight, probably painted shut. She tugged on the window to try and stop the cold from blowing in. The window rattled against the unstable frame and the soft wood of the sill.

She began to hear music from another part of the house. Chopin’s Nocturn, opus nine, number two in e-flat Major. She couldn’t tell who was playing.

Grady unlocked the door and entered, bearing a sandwich and a glass of water. “Does the music surprise you?”

“Why would it?”

“A roughneck like me digging classical music?”

“Oh, please stop. You told me you wanted to study music, remember?”

“Which composers do you dislike?

Emily thought a moment. She could guess where this was going. “Vivaldi and Bach.”

“Vivaldi and Bach? That’s weird.”

“Vivaldi is too wishy-washy, and Bach is too somber. They’re opposites.”

Grady smirked. “I guess you know what you’ll be hearing a lot of.”

He left and locked the door. Emily curled up on the bed. If nothing else, she would hear two of her favorites. A tiny victory, but maybe she could do better.

Emily was too nervous to eat the sandwich Grady left for her. She wrapped it in the napkin he brought with it and went into the little bathroom. She found soap, 2 in 1 shampoo, toothpaste and a toothbrush. How long had Grady been planning this? She brushed her teeth, waited until the water was warm enough to wash her face and went back to the bed.

She curled up in the thin blanket. What was going to happen to her? How long would it take before people noticed? Charles was expecting her at his apartment. She’d taken him up on his invitation to move in with him when Grady’s behavior began to scare her. He must have called.

She could see nothing out of the frosted window. It was full dark. Where was she, was she still in Boston? Despair iced the bottom of her stomach. She gave herself up to the Chopin, riding the rhythms like a wave. Somewhere in the world there was still beauty.

After a fitful sleep, she saw that morning had greyed the window. She looked out, hoping to orient herself. Without her watch or cell phone she had no idea of the time, but it looked past dawn. Puffs of white dotted the streets; people had already started warming up their cars. She saw well-kept two-family houses and clean sidewalks. Did this house share a wall with a neighbor? Could she make enough noise when Grady left to alert someone?

She could at least keep track of the days (dear Lord, do I have to think of staying days in this house?). Yesterday was Monday, today was Tuesday. She was scheduled to be at work at 9 a.m. At least she wasn’t scheduled to work an evening. She’d be missed as soon as the library opened.

Leaving the window, her hand brushed against a splinter. “Ooh, that hurts! That’s my job for today, digging out a splinter.” Suddenly she drew her hand against the windowsill. It was soft, unpainted, probably rotten, as was the wood around the window. The glass rattled when the wind blew. “No, that’s my job for today. I’m going to open this window and get out of Dodge.”

She searched the dresser for something she could use to pry the window open. She found dust, handkerchiefs wedged in the back of the top drawer. Forgotten cufflinks. The second drawer held extra towels.

She moved to the wardrobe. There were a handful of hangers on the rod and more dust on the floor. Would a hanger work? She was about to shut the door when she saw, in the corner, a rag and a putty knife. At one time somebody was going to fix the window. She grabbed the knife and slipped it into the pillowcase just as Grady knocked on the door.

“You decent?”

“Just a second.” Emily wrapped the blanket around herself. “OK.”

Grady entered with a tray holding buttered toast and coffee. “I see you didn’t eat last night. You better eat now.”

“Can I have my clothes, please? This room’s cold.”

“No. And don’t try anything while I’m at work. I’ll know.”

“How long are you going to keep me here?”

Grady didn’t answer, just locked the door. He returned with a sandwich in a Baggie, an apple and a water bottle. “Stay out of trouble.”

He locked the door again. Somewhere she heard a toilet flushing and water running. Then the front door closed, and she heard a car starting, then driving off.

Emily drank the coffee and ate the edges of the toast. So much butter glopped on it! Maybe she could use it to grease the window frame.

What to do? Keep as normal a life as possible. She took a shower while the hot water lasted and brushed her teeth. Remake the bed. Remove the putty knife from the pillowcase. How to attack the problem? She started prying the bottom of the window. The wood must be loose if it rattled and let in frigid air. She worked away at the softness of the windowsill, then ran the knife around the edges of the window frame. Sill, right frame, left frame, sill right frame, left frame, was this working at all? Yes, small splinters and dust were falling at her feet.

Sill, right frame, left frame. She worked until her arms and shoulders ached, then stopped for lunch. Baloney and mayonnaise. Ugh. At least the apple wasn’t greasy. She drank some water.

She fell asleep for an hour. She hadn’t slept well last night. She worked away at the window until she heard a car pull up. Grady. Would he see what she was trying to do? She grabbed a towel from the dresser and threw it over the window. It hung precariously over the window frame.

Grady knocked at the door, then let himself in. “So, you survived.”

“Just barely. Please let me go.”

“Maybe. Maybe when you learn what it’s like to be alone.”

Emily’s throat felt thick, her eyes hot. Would tears help? Probably not, he’d be happy to see her break.

Soon Grady came up again, to collect the lunch tray and leave dinner. A grinder with cold cuts, cheese and more mayonnaise, and a small stack of oatmeal cookies. Did he ever make the acquaintance of a green vegetable?

He noticed the towel over the window. “What’s that for?”

“The window lets the cold in.”

“Sorry the accommodations don’t suit you, Lady Di.”

He left and locked the door. “If-when, not if, I get out of here I will try to hurt you. Somehow,” she thought furiously. Good. The anger was better than despair. It gave her more energy.

She heard water running in what she thought was the kitchen. Then music played. Vivaldi. The Four Seasons. “That didn’t take long.” She returned to the bed, wrapped herself in the blanket and let herself find the music. She pictured the seasons, each so different, so clearly drawn by the music. When the Vivaldi stopped, she heard Jim Morrison, then Robbie Robertson. Well, that’s a change. She imagined them in their prime, such beautiful, sensuous boys. Again the music found her, this time as slender spinners of song, seducing the crowd with their voices and guitars, played into the night.

The next grey dawn came, as did Grady, more toast, more coffee. He dropped the tray as he left, it clattered against the dresser. Under the cover of the noise, Emily slipped toward the door on bare feet. Not quietly enough. She was pulled back by her hair. Grady pushed her on the bed.

“I told you, don’t try anything. Now sit there and eat,”

Emily tried to eat. At least the toast had jelly today, not globs of butter. Grady came back as she was finishing. He dropped another hospital gown on the bed.

“This one’s a little thicker. Maybe you’ll stop whining about the cold.”

“Where did you get these?”

“I took my mother here the last week before she died. The hospital gave them to us before we left.”

“I’m sorry. That must have been hard.”

“Yeah.” Grady left, locking the door behind him,

The gown was thicker, more like a scrub gown that would be worn in the operating room. So, his mother died in his care. That was one piece of Grady’s alone-ness. That and being held apart from the music he loved, only to serve its practitioners, often without thanks or notice. She’d seen how often people didn’t notice the ones who made the Conservatory go, maintenance people, kitchen workers, cleaners. These were the people who supported the talent, the aura of music that surrounded the campus. Professors, students, their eyes slipped over the others like water. Could she use this understanding, create rapport?

She couldn’t stop to think. She had a schedule to keep, such as it was. Shower, shampoo, tooth brushing. Livid bruises were starting to show where Grady had grabbed her arms. She washed her underthings, squeezed them in a towel and draped them over the heater vent. She could do violence for a little lip gloss and body lotion.

Dressed in her new attire for the day, she made her bed and resumed her position at the window, working away at the soft wood. It was softer now; more dust was falling. She must be sure to get rid of it before Grady got back.

The evening passed like the one before. A burger and fries tonight, with lettuce and tomato, woo-hoo! Grady had forgotten to leave lunch, so she was hungry. He came up to collect the tray, curt and uncomfortable after the morning’s upset.

Water running in the kitchen, then the music. Bach, tonight, D-Minor Partita, He thought he was paying her back for her behavior today. But she was lost in the music, held by its powerful perfection. How could anyone despair when surrounded by such structured beauty?

She found she could sleep tonight, holding on to the spell of the music and after working at the window most of the day. Her arms ached, from scraping all day and from the darkening bruises on her arms. Sleep would keep her from thinking.

Dawn was brighter the next morning. She was at the window again after Grady left for work, but two hours later she heard the front door open again. Heavy footsteps stopped, then pounded to the door. “

Grady unlocked the door. His face was red. “The police came to see me today, about you. They want to search the house.” He showed her a pistol. “Not a word from you. Do you hear me? I have enough bullets to take care of us all.” He thrust the pistol into her hand. “It’s real, all right. Not one word. Not one sound.”

He grabbed her and pushed her into the wardrobe. The door closed on her, just. There was a knock at the front door. Grady left the room.

She heard voices and movement in the house. Was Grady telling the truth? Was his rage enough to drive him to shooting? She began to cry, then stuffed a fist in her mouth. No, she couldn’t risk it.

He hadn’t locked the door to the room. Of course not, it would look suspicious. Could she try to sneak out? She had seen nothing of the rest of the house, didn’t know where an exit could be.

The voices moved to the door, and it opened. “Just like everything else.” Grady said. “She’s not here.”

“Where do you think she might be?” Another voice. “You sure were keeping track of her for a while.”

“I don’t know. Did you ask the boyfriend? I heard she had one.”

“We’ve had plenty of chances to do that, he calls the station at least twice a day.” The voice paused. “If you know anything, it’s best for you to let us know.”

“I tell you, I don’t know. I’m done with her,”

The voices moved away. The front door closed. Her hope of escape with the police was gone. Should she have risked calling out? She began to cry.

Footsteps came back, one set. Grady opened the wardrobe door. “You did good. You can have some Mozart tonight. What’s wrong?”

“I want to go home. Please, “ she stammered.

“I’ll bring back some pasta tonight. The Italian place around the corner is really good.”

“I want to go home. Please.”

He waited a moment, then turned and locked the door. Emily lay down on the bed, too spent to work at the window any more today, too despairing. But Grady had promised her Mozart. That evening she heard Piano Sonata 16. Lively and graceful, the music kept her spirits high enough to help her hold together.

But Thursday came, a brighter dawn. She had to be done by Friday. Grady had been at work all week, he would be off on Saturday, She couldn’t risk doing anything if he was going to be at the house.

Breakfast, lunch left for her, Grady gone. She flew through her morning routines, then was back at the window. She didn’t stop for lunch. She kept at it, kept at the softening wood of the sill and the frame. And then it happened. The frame came away from the window. There was a small space between the sill and the glass.

Could she lift it? After all this work, was she still a prisoner? She pressed at the window. God it was tight! She pressed harder, and harder. Her muscles began to scream. She needed to stop to wipe the sweat from her hands. She pressed until there was enough space to let her out. Cold, fresh air blew in. She grabbed the blanket and prepared to make the leap. went out of the window, the blanket tangling in a bush under the window. She quickly worked it loose and then wrapped it around her. She walked quickly to the house next door, the cold ground like iron under her bare feet.

Emily rang the bell at the back door. Two cars were in the driveway, certainly somebody was home. She tightened the blanket around her. She must look insane, barefoot, blanket-clad, hair blown.

An aging man came to the door. “I’m Emily. Please, can you help me? I’ve been in danger. Can you call the police for me? The man stared blankly. “Please, just call the police and I won’t bother you. I can’t stay long in this cold.”

Recognition dawned in the man’s eyes. “You’re the librarian they’ve been looking for.”

“Yes!” Emily cried.

“I must be crazy, keeping you out in the cold. Come in.”

The warm house felt wonderful. The man was a retired machinist, Peter Prentice, and his wife was Mary Prentice. Mary went into action as Peter called the police, warming up coffee and, seeing Emily’s discomfort in her blanket, leant her a pair of sweats and sneakers. Emily was enveloped in a kindness even warmer than the room.

A police cruiser pulled in the driveway. Leaving with the police, Emily watched as Grady’s house disappeared from view.

Soon they were at the police station, Police District 5-West. She had been in Roslindale all the time. She was shown into an interrogation room, where she began the process of unwinding all that had happened. She told it all, even as the memories sickened her, Grady’s seeming friendliness, his anger at being turned down and finally his taking her to his house. Roslindale. Just six miles, a little more than 30 minutes from the Conservatory.

She told the officers about the police coming to question him, about the gun. She told them about her work at the window, scraping away at the rotted wood, and about the charitable couple who had helped her.

Suddenly she heard a familiar voice. “Try Room 2, to the left.” Steps coming down the hall. Charles bursting into the room, despite the protests from the officers.

But she was in his arms, Charlie, so real, tousled brown hair, blue eyes, the scent of soap and clean wool. “I thought I would never see you again,” she sobbed.

But she had. In the following weeks she got her life in balance again. The library offered her time off, but she needed to get back what she had lost. She was anxious on campus, but there was little reason. Grady had given up and confessed. Out on bail, even if he tried to come on campus security would keep him away. The District Attorney told her he would likely receive considerable prison time. She clung to Charles at first, then let go, happy to just be with him. She began to see friends, to laugh again.

When she had a moment, she felt a tiny spark of compassion for Grady, who had been kept from music, overlooked at work, who had been alone. He’d turned his misery toward her, but at least she could acknowledge that misery. Sometimes, despite our best efforts, life kept us unbalanced. All she could do was work to keep her balance and try to have some empathy for those who could not.

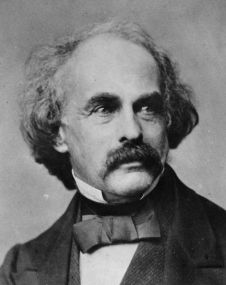

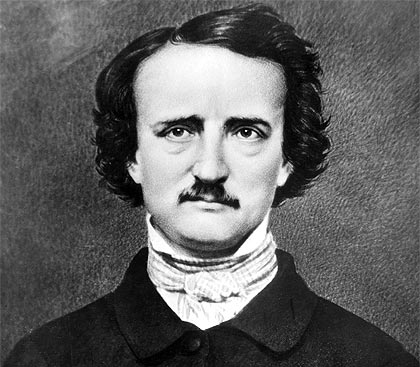

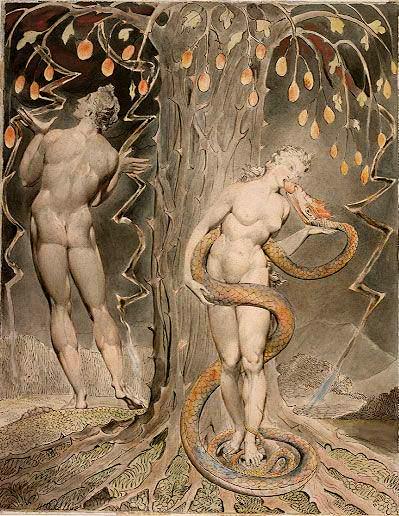

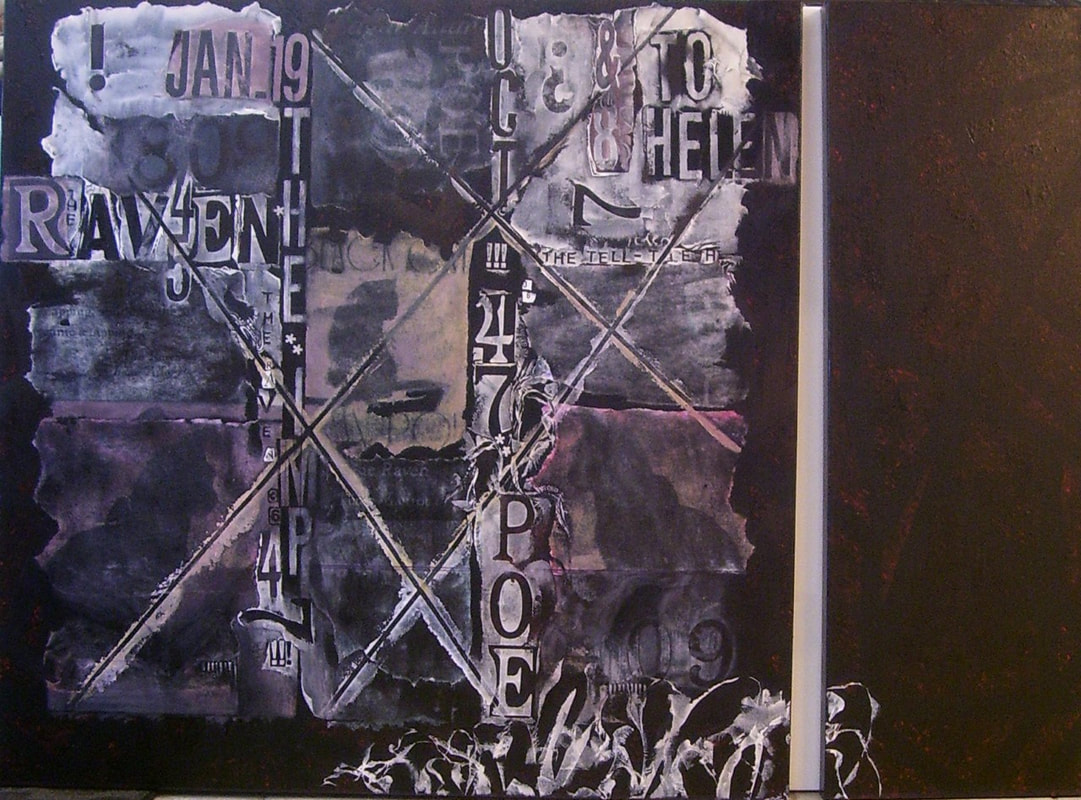

The Sphinx

By Edgar Allan Poe

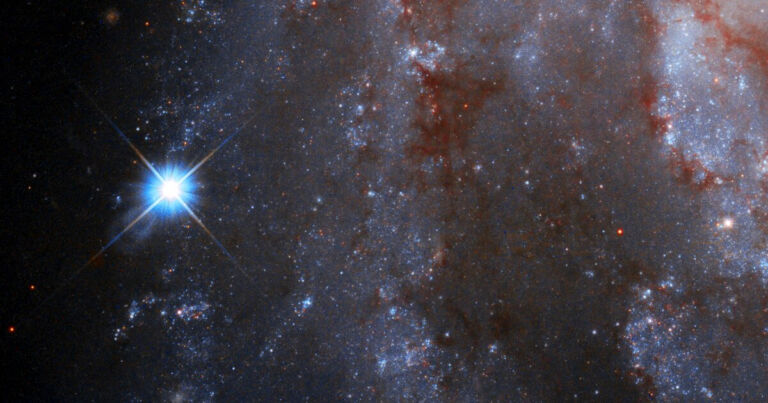

During the dread reign of the Cholera in New York, I had accepted the invitation of a relative to spend a fortnight with him in the retirement of his cottage orné on the banks of the Hudson. We had here around us all the ordinary means of summer amusement; and what with rambling in the woods, sketching, boating, fishing, bathing, music and books, we should have passed the time pleasantly enough, but for the fearful intelligence which reached us every morning from the populous city. Not a day elapsed which did not bring us news of the decease of some acquaintance. Then, as the fatality increased, we learned to expect daily the loss of some friend. At length we trembled at the approach of every messenger. The very air from the South seemed to us redolent with death. That palsying thought, indeed, took entire possession of my soul. I could neither speak, think, nor dream of any thing else. My host was of a less excitable temperament, and, although greatly depressed in spirits, exerted himself to sustain my own. His richly philosophical intellect was not at any time affected by unrealities. To the substances of terror he was sufficiently alive, but of its shadows he had no apprehension.

His endeavors to arouse me from the condition of abnormal gloom into which I had fallen, were frustrated in great measure, by certain volumes which I had found in his library. These were of a character to force into germination whatever seeds of hereditary superstition lay latent in my bosom. I had been reading these books without his knowledge, and thus he was often at a loss to account for the forcible impressions which had been made upon my fancy.

A favorite topic with me was the popular belief in omens — a belief which, at this one epoch of my life, I was almost seriously disposed to defend. On this subject we had long and animated discussions — he maintaining the utter groundlessness of faith in such matters. — I contending that a popular sentiment arising with absolute spontaneity — that is to say without apparent traces of suggestion — had in itself the unmistakable elements of truth, and was entitled to as much respect as that intuition which is the idiosyncracy of the individual man of genius.

The fact is, that soon after my arrival at the cottage, there had occurred to myself an incident so entirely inexplicable, and which had in it so much of the portentious character, that I might well have been excused for regarding it as an omen. It appalled, and at the same time so confounded and bewildered me, that many days elapsed before I could make up my mind to communicate the circumstances to my friend.

Near the close of an exceedingly warm day, I was sitting, book in hand, at an open window, commanding, through a long vista of the river banks, a view of a distant hill, the face of which nearest my position, had been denuded, by what is termed a land-slide, of the principal portion of its trees. My thoughts had been long wandering from the volume before me to the gloom and desolation of the neighboring city. Uplifting my eyes from the page, they fell upon the naked face of the hill, and upon an object — upon some living monster of hideous conformation, which very rapidly made its way from the summit to the bottom, disappearing finally in the dense forest below. As this creature first came in sight, I doubted my own sanity — or at least the evidence of my own eyes; and many minutes passed before I succeeded in convincing myself that I was neither mad nor in a dream. Yet when I describe the monster, (which I distinctly saw, and calmly surveyed through the whole period of its progress,) my readers, I fear, will feel more difficulty in being convinced of these points than even I did, myself.

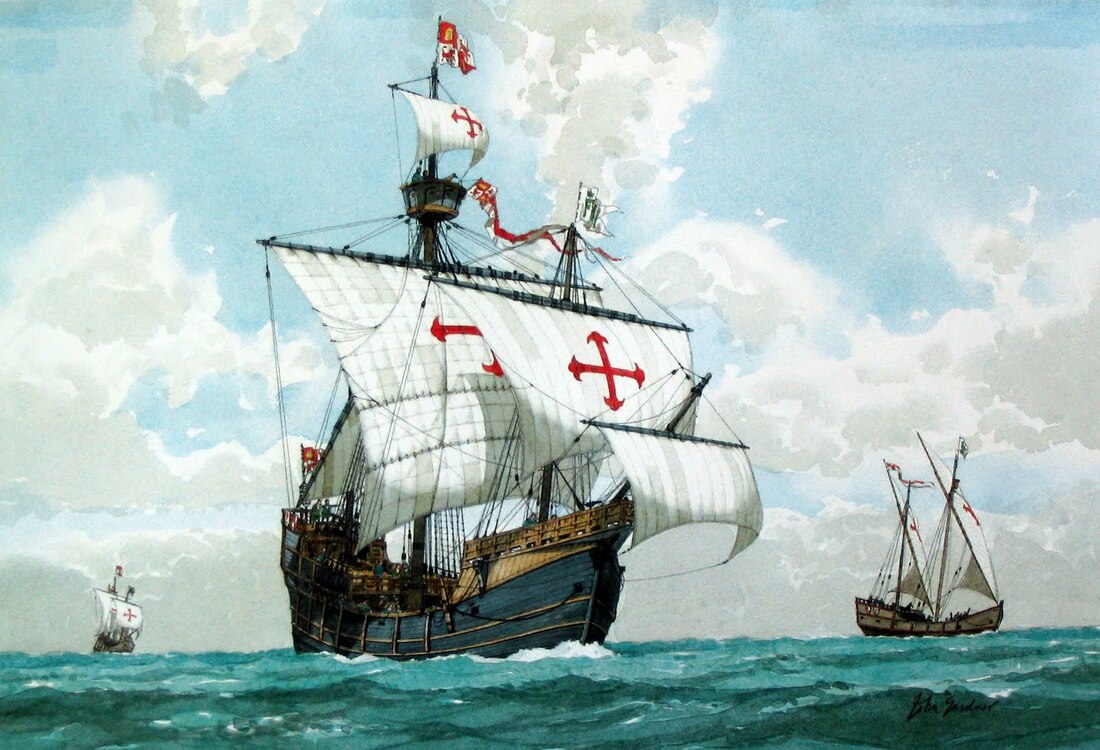

Estimating the size of the creature by comparison with the diameter of the large trees near which it passed — the few giants of the forest which had escaped the fury of the land-slide — I concluded it to be far larger than any ship of the line in existence. I say ship of the line, because the shape of the monster suggested the idea — the hull of one of our seventy-fours might convey a very tolerable conception of the general outline. The mouth of the animal was situated at the extremity of a proboscis some sixty or seventy feet in length, and about as thick as the body of an ordinary elephant. Near the root of this trunk was an immense quantity of black shaggy hair — more than could have been supplied by the coats of a score of buffalos; and projecting from this hair downwardly and laterally, sprang two gleaming tusks not unlike those of the wild boar, but of infinitely greater dimension. Extending forward, parrallel with the proboscis, and on each side of it was a gigantic staff, thirty or forty feet in length, formed seemingly of pure crystal, and in shape a perfect prism: — it reflected in the most gorgeous manner the rays of the declining sun. The trunk was fashioned like a wedge with the apex to the earth. From it there were outspread two pairs of wings — each wing nearly one hundred yards in length — one pair being placed above the other, and all thickly covered with metal scales; each scale apparently some ten or twelve feet in diameter. I observed that the upper and lower tiers of wings were connected by a strong chain. But the chief peculiarity of this horrible thing, was the representation of a Death’s Head, which covered nearly the whole surface of its breast, and which was as accurately traced in glaring white, upon the dark ground of the body, as if it had been there carefully designed by an artist. While I regarded this terrific animal, and more especially the appearance on its breast, with a feeling of horror and awe — with a sentiment of forthcoming evil, which I found it impossible to quell by any effort of the reason, I perceived the huge jaws at the extremity of the proboscis, suddenly expand themselves, and from them there proceeded a sound so loud and so expressive of wo, that it struck upon my nerves like a knell, and as the monster disappeared at the foot of the hill, I fell at once, fainting, to the floor.

Upon recovering, my first impulse of course was to inform my friend of what I had seen and heard — and I can scarcely explain what feeling of repugnance it was, which, in the end, operated to prevent me.

At length, one evening, some three or four days after the occurrence, we were sitting together in the room in which I had seen the apparition — I occupying the same seat at the same window, and he lounging on a sofa near at hand. The association of the place and time impelled me to give him an account of the phenomenon. He heard me to the end — at first laughed heartily — and then lapsed into an excessively grave demeanor, as if my insanity was a thing beyond suspicion. At this instant I again had a distinct view of the monster — to which, with a shout of absolute terror, I now directed his attention. He looked eagerly — but maintained that he saw nothing — although I designated minutely the course of the creature, as it made its way down the naked face of the hill.

I was now immeasurably alarmed, for I considered the vision either as an omen of my death, or, worse, as the fore-runner of an attack of mania. I threw myself passionately back in my chair, and for some moments buried my face in my hands. When I uncovered my eyes, the apparition was no longer apparent.

My host, however, had in some degree resumed the calmness of his demeanor, and questioned me very vigorously in respect to the conformation of the visionary creature. When I had fully satisfied him on this head, he sighed deeply, as if relieved of some intolerable burden, and went on to talk, with what I thought a cruel calmness of various points of speculative philosophy, which had heretofore formed subject of discussion between us. I remember his insisting very especially (among other things) upon the idea that a principle source of error in all human investigations, lay in the liability of the understanding to under-rate or to over-value the importance of an object, through mere mis-admeasurement of its propinquity. “To estimate properly, for example,” he said, “the influence to be exercised on mankind at large by the thorough diffusion of Democracy, the distance of the epoch at which such diffusion may possibly be accomplished, should not fail to form an item in the estimate. Yet can you tell me one writer on the subject of government, who has ever thought this particular branch of the subject worthy of discussion at all?”

He here paused for a moment, stepped to a book-case, and brought forth one of the ordinary synopses of Natural History. Requesting me then to exchange seats with him, that he might the better distinguish the fine print of the volume, he took my arm chair at the window, and, opening the book, resumed his discourse very much in the same tone as before.

“But for your exceeding minuteness,” he said, “in describing the monster, I might never have had it in my power to demonstrate to you what it was. In the first place, let me read to you a school boy account of the genus Sphinx, of the family Crepuscularia, of the order Lepidoptera, of the class of Insecta — or insects. The account runs thus:

“ ‘Four membranous wings covered with little colored scales of a metallic appearance; mouth forming a rolled proboscis, produced by an elongation of the jaws, upon the sides of which are found the rudiments of mandibles and downy palpi; the inferior wings retained to the superior by a stiff hair; antennæ in the form of an elongated club, prismatic; abdomen pointed. The Death’s-headed Sphinx has occasioned much terror among the vulgar, at times, by the melancholy kind of cry which it utters, and the insignia of death which it wears upon its corslet.’ ”

He here closed the book and leaned forward in the chair, placing himself accurately in the position which I had occupied at the moment of beholding “the monster.”

“Ah, here it is!” he presently exclaimed — “it is reascending the face of the hill, and a very remarkable looking creature, I admit it to be. Still, it is by no means so large or so distant as you imagined it; for the fact is that, as it wriggles its way up this hair, which some spider has wrought along the window-sash, I find it to be about the sixteenth of an inch in its extreme length, and also about the sixteenth of an inch distant from the pupil of my eye!”

War

By Sherwood Anderson

The story came to me from a woman met on a train. The car was crowded and I took the seat beside her. There was a man in the offing who belonged with her–a slender girlish figure of a man in a heavy brown canvas coat such as teamsters wear in the winter. He moved up and down in the aisle of the car, wanting my place by the woman’s side, but I did not know that at the time.

The woman had a heavy face and a thick nose. Something had happened to her. She had been struck a blow or had a fall. Nature could never have made a nose so broad and thick and ugly. She had talked to me in very good English. I suspect now that she was temporarily weary of the man in the brown canvas coat, that she had travelled with him for days, perhaps weeks, and was glad of the chance to spend a few hours in the company of some one else.

Everyone knows the feeling of a crowded train in the middle of the night. We ran along through western Iowa and eastern Nebraska. It had rained for days and the fields were flooded. In the clear night the moon came out and the scene outside the car-window was strange and in an odd way very beautiful.

You get the feeling: the black bare trees standing up in clusters as they do out in that country, the pools of water with the moon reflected and running quickly as it does when the train hurries along, the rattle of the car-trucks, the lights in isolated farm-houses, and occasionally the clustered lights of a town as the train rushed through it into the west.

The woman had just come out of war-ridden Poland, had got out of that stricken land with her lover by God knows what miracles of effort. She made me feel the war, that woman did, and she told me the tale that I want to tell you.

I do not remember the beginning of our talk, nor can I tell you of how the strangeness of my mood grew to match her mood until the story she told became a part of the mystery of the still night outside the car- window and very pregnant with meaning to me.

There was a company of Polish refugees moving along a road in Poland in charge of a German. The German was a man of perhaps fifty, with a beard. As I got him, he was much such a man as might be professor of foreign languages in a college in our country, say at Des Moines, Iowa, or Springfield, Ohio. He would be sturdy and strong of body and given to the eating of rather rank foods, as such men are. Also he would be a fellow of books and in his thinking inclined toward the ranker philosophies. He was dragged into the war because he was a German, and he had steeped his soul in the German philosophy of might. Faintly, I fancy, there was another notion in his head that kept bothering him, and so to serve his government with a whole heart he read books that would re-establish his feeling for the strong, terrible thing for which he fought. Because he was past fifty he was not on the battle line, but was in charge of the refugees, taking them out of their destroyed village to a camp near a railroad where they could be fed.

The refugees were peasants, all except the woman in the American train with me, her lover and her mother, an old woman of sixty-five. They had been small landowners and the others in their party had worked on their estate.

Along a country road in Poland went this party in charge of the German who tramped heavily along, urging them forward. He was brutal in his insistence, and the old woman of sixty-five, who was a kind of leader of the refugees, was almost equally brutal in her constant refusal to go forward. In the rainy night she stopped in the muddy road and her party gathered about her. Like a stubborn horse she shook her head and muttered Polish words. “I want to be let alone, that’s what I want. All I want in the world is to be let alone,” she said, over and over; and then the German came up and putting his hand on her back pushed her along, so that their progress through the dismal night was a constant repetition of the stopping, her muttered words, and his pushing. They hated each other with whole-hearted hatred, that old Polish woman and the German.

The party came to a clump of trees on the bank of a shallow stream and the German took hold of the old woman’s arm and dragged her through the stream while the others followed. Over and over she said the words: “I want to be let alone. All I want in the world is to be let alone.”

In the clump of trees the German started a fire. With incredible efficiency he had it blazing high in a few minutes, taking the matches and even some bits of dry wood from a little rubber-lined pouch carried in his inside coat pocket. Then he got out tobacco and, sitting down on the protruding root of a tree, smoked and stared at the refugees, clustered about the old woman on the opposite side of the fire.

The German went to sleep. That was what started his trouble. He slept for an hour and when he awoke the refugees were gone. You can imagine him jumping up and tramping heavily back through the shallow stream and along the muddy road to gather his party together again. He would be angry through and through, but he would not be alarmed. It was only a matter, he knew, of going far enough back along the road as one goes back along a road for strayed cattle.

And then, when the German came up to the party, he and the old woman began to fight. She stopped muttering the words about being let alone and sprang at him. One of her old hands gripped his beard and the other buried itself in the thick skin of his neck.

The struggle in the road lasted a long time. The German was tired and not as strong as he looked, and there was that faint thing in him that kept him from hitting the old woman with his fist. He took hold of her thin shoulders and pushed, and she pulled. The struggle was like a man trying to lift himself by his boot straps. The two fought and were full of the determination that will not stop fighting, but they were not very strong physically.

And so their two souls began to struggle. The woman in the train made me understand that quite clearly, although it may be difficult to get the sense of it over to you. I had the night and the mystery of the moving train to help me. It was a physical thing, the fight of the two souls in the dim light of the rainy night on that deserted muddy road. The air was full of the struggle and the refugees gathered about and stood shivering. They shivered with cold and weariness, of course, but also with something else. In the air everywhere about them they could feel the vague something going on. The woman said that she would gladly have given her life to have it stopped, or to have someone strike a light, and that her man felt the same way. It was like two winds struggling, she said, like a soft yielding cloud become hard and trying vainly to push another cloud out of the sky.

Then the struggle ended and the old woman and the German fell down exhausted in the road. The refugees gathered about and waited. They thought something more was going to happen, knew in fact something more would happen. The feeling they had persisted, you see, and they huddled together and perhaps whimpered a little.

What happened is the whole point of the story. The woman in the train explained it very clearly. She said that the two souls, after struggling, went back into the two bodies, but that the soul of the old woman went into the body of the German and the soul of the German into the body of the old woman.

After that, of course, everything was quite simple. The German sat down by the road and began shaking his head and saying he wanted to be let alone, declared that all he wanted in the world was to be let alone, and the Polish woman took papers out of his pocket and began driving her companions back along the road, driving them harshly and brutally along, and when they grew weary pushing them with her hands.

There was more of the story after that. The woman’s lover, who had been a school-teacher, took the papers and got out of the country, taking his sweetheart with him. But my mind has forgotten the details. I only remember the German sitting by the road and muttering that he wanted to be let alone, and the old tired mother-in-Poland saying the harsh words and forcing her weary companions to march through the night back into their own country.

Benjamin’s Lure

by

James Nelli

The only thing breaking the mirrored surface of the water in Teller’s Cove on Lake Moultrie in South Carolina was the V-shaped wake of Benjamin Adler’s slow moving bass boat. The cool onshore breeze, bald cypress trees, and low-lying clouds illuminated by a fiery orange setting sun created another perfect late afternoon fishing adventure for Benjamin. After 47 years working on Wall Street as a successful executive at a venture capital company, Benjamin was happily retired. All he needed now to fill his days trolling the coves of Lake Moultrie in his bass boat were two cheese sandwiches, a bag of turkey jerky, a few cold bottles of Heineken, an ice filled cooler, and an ever-expanding variety of fishing lures and lines designed to help him catch fish. But not just any fish. He was searching for the king of freshwater fish, the largemouth bass. These bass are not big, maybe 12 pounds, but they are intelligent, strike a lure with explosive force, and they would fight and fight and fight. These were all the characteristics Benjamin wanted in a fishing adventure on Lake Moultrie.

Benjamin’s late afternoon fishing adventure had yielded very little tangible results. Other than a couple of weak nibbles and having a leader-line break after getting snagged on a stump that sent his favorite blue and gray spinnerbait lure to the bottom of Lake Moultrie, the afternoon

had been uneventful. That must be why people say it’s called fishing, not catching. Sometimes despite all your preparation, all your knowledge, you still don’t catch anything. It happens. As Benjamin was getting packed up to head back home, he noticed a young boy watching him from the other side of the cove. Benjamin started to raise his hand to wave at the boy, but the boy had already disappeared back into the woods beyond the cove. He thought it was odd that anyone was out this far near the lake without a boat, because there weren’t any homes in that part of the cove. But that thought passed quickly. Time to get back to his wife, Beth, at their lakeside home for dinner.

Benjamin moored the bass boat to the dock and walked toward the house with the empty ice chest. Beth saw him coming and could tell by the expression on his face that they were having frozen fish for dinner tonight. It wasn’t a new experience, but she was hoping for a better outcome.

“No problem, we’ve still got a few bass filets from your catch of last week,” Beth said before Benjamin even made it to the front door.

“I thought I had it figured out Beth,” replied Benjamin as he sat down on the couch opposite an already robust fire in the fireplace.

Beth brought two generously filled wine glasses to the couch and handed one to Benjamin and kept one for herself. “Did you enjoy your time on the lake?”

“Other than coming home empty-handed, the lake and the evening sky were especially beautiful today. I think I’m getting used to this retirement thing. You should come out on the boat with me.”

“I might Ben, but that’s your thing. You know I like driving into town and volunteering at the clinic. There are a lot of people in this area that need help. It’s my way of giving back.”

Before she and Benjamin retired and moved to South Carolina, Beth had been a maternity nurse at Bethany General Hospital in Greenwich, Connecticut. For a variety of medical reasons, Benjamin and Beth could not have children. Working at the hospital helping new mothers had filled a need for Beth that only she could describe.

“I did have something interesting happen just before I headed back home today,” said Ben.

“What was that?”

“As I was packing up, I saw a young boy maybe fourteen or fifteen years old watching me from the bank of the lake.”

“What’s so strange about that?”

“Well, I don’t know of any homes in that area. I’m not sure where he came from. When I tried to get his attention, he disappeared into the woods.”

“That is strange. Maybe you’ll see him tomorrow?”

“Maybe.”

The timer on the oven signaled dinner was ready. Benjamin picked up the two wine glasses and brought them to the dining room table along with the half-full bottle of wine. He was already thinking about tomorrow’s adventure.

The next afternoon, Benjamin boarded his bass boat and headed out an hour earlier than normal. He was anxious to try out another line and lure combination, and possibly see the mysterious young boy again. The low hum of his trolling motor was the only sound that

accompanied Benjamin to his favorite Teller’s Cove fishing site. He dropped his fluke anchor offshore and settled in for what he hoped would be a successful fishing adventure. After an hour of fishing, Benjamin hadn’t seen a substantial change from the results of the day before. He was getting frustrated, but he still couldn’t imagine anywhere else he’d rather be. As he pulled his line in and prepared for another cast, he saw the young boy appear on the shore. Benjamin waved, and the boy smiled and waved Benjamin toward the shore. Benjamin raised his anchor and trolled to the boy onshore. The boy was slender and looked about 15 years old. He was barefoot, had shaggy black hair, and was wearing brown shorts and a plain tan tee shirt. Benjamin also noticed a large light skin patch on the boy’s otherwise tan face. It was some sort of skin discoloration, possibly a birth mark. The irregular shaped patch ran from the boy’s left ear down his left cheek to the base of his jaw.

“How are you young man,” asked Benjamin.

“I’m fine sir.”

“My name is Mr. Adler. What’s your name?”

“Good to meet you sir. My name is Noah. Any luck fishing today?”

“I’ve had better days, but I keep trying. I saw you here yesterday. Are you from around here?”

“Oh yes. I’m from over there,” said the boy pointing back into the wooded area behind him.

“Do you fish out here?” asked Benjamin.

“Sometimes I do. Do you want to see what lure I use?”

“Of course. As you can see, I can use all the help I can get. I lost my favorite blue and gray spinnerbait lure here at the lake yesterday. I got it caught in the weeds and broke the leader line trying to pull it loose. It’s now at the bottom of the lake.”

“Sorry to hear that sir.”

The young boy reached into a zippered pouch he had on his waistband and pulled out a raggedy looking fuzzy jig lure, walked into the water toward the boat, and handed it to Benjamin.

“You catch fish with this lure?” asked a smiling but skeptical Benjamin as he examined the tattered lure in his hand.

“I do, and it’s great for the big fish like the largemouth bass,” Noah proudly proclaimed.

That comment got the attention of Benjamin.

“Why don’t you try it, sir? See for yourself.”

Benjamin smiled, leaned forward, and began to pass the tattered jig lure back to the young boy, but quickly pulled his hand back. “Thanks, I think I will try it.”

With the help of the young boy, Benjamin pushed the small boat away from the shore and trolled back out to the center of Teller’s Cove. He dropped anchor and then attached the tattered lure to his leader line. As he examined his new setup, he could see that this was a main line/leader line and lure combination he would never put together himself. It seemed all wrong, but he was determined to try anything at this time.

Benjamin’s first cast went only a few yards into the center of the cove. He slowly reeled it in but got no bites. When he got the lure back to the boat, he looked over at the young boy. The

boy smiled back and signaled to Benjamin to try it again. This time Benjamin’s cast went further into the cove, broke the surface of the water, and was immediately struck by a big fish. Benjamin reeled down his pole to get the slack out of the line, aggressively set the hook, and began reeling in what Benjamin could see was a largemouth bass. This was all being done under the watchful eye and cheers of the young boy. As soon as the bass was near enough to the boat, Benjamin used a landing net to get the large fish into the boat and secured it in the ice filled cooler. Working quickly, he again cast his line into the lake. Bam! Another powerful strike and more cheers from the young boy on the shore. This happened six times in a row, and the only reason Benjamin stopped fishing was that he ran out of room for any more fish in his cooler. He had never done that before. Benjamin secured his equipment in the boat and looked back toward shore to return the lure to his young friend; however, the young boy had surprisingly already left the cove.

Benjamin returned home to Beth with an ice chest full of largemouth bass and told her the story of Noah and the lure. They talked all through dinner. Sometimes shaking their heads on how unbelievable the entire day was.

“You know Beth, we will never be able to eat all these fish ourselves. Why don’t we try to find the boy and his family and bring some of the fish to them? Without his lure, none of this would have happened.”

“I like that idea, Ben. Why don’t you come with me to the clinic tomorrow morning, and we’ll talk to Dr. Cunningham. He’s been in this area for over 20 years, and he knows everybody. I’m sure he’ll be able to help us.”

“That’s a great idea. Let’s take some time tonight to clean, filet, and freeze a few of the fish so we can give them to Noah’s family tomorrow. Let’s get started.”

Early the next morning, Beth and Benjamin drove to the clinic with an ice chest full of bass filets for Noah and his family. Dr. Cunningham was just beginning his shift and greeted Beth and Benjamin at the clinic entrance.

“Good morning, Beth. What’s got you here so early?”

“Dr. Cunningham, this is my husband Benjamin, and we have a favor to ask.”

Benjamin spoke first. “Yesterday, I was out on Lake Moultrie in Teller’s Cove fishing for largemouth bass.”

“Great spot. I’ve fished there a few times myself,” said a smiling Dr. Cunningham.

“Good, so you’re familiar with the spot. Anyway, I came across a young boy in the cove who loaned me a lure that helped me catch more bass than I had ever caught before. Well, now we’ve got more fish than we could ever eat ourselves, and I’d like to share the catch with the boy and his family and return the lure. Think you can help?”

“I’ll try. Did you get the boy’s name?”

“He said his name was Noah.”

“That’s a very common name in this area. Did he tell you his last name?” said a smiling Dr. Cunningham.

“No, but he did have a distinguishing discoloration on his face. It was a light irregular skin patch that ran from below his left ear to the base of his jaw.”

Dr. Cunningham’s smile disappeared, and his face turned serious. “How old do you think this boy was?”

“I’d say he was about 14 or 15 years old. No older than that. Can you help us find him?”

“I can. Let me drive you there but leave the frozen fish here. We’ll pick it up later.”

Benjamin and Beth rode in Dr. Cunningham’s car to a spot about ten minutes outside of town. There was no conversation during the ride, and the atmosphere within the car could only be described as tense. Except for a few glances between Benjamin and Beth there was no eye contact with Dr. Cunningham. Dr. Cunningham pulled the car up to a low wrought iron fence with no houses anywhere in the area and shut off the engine.

“We’re here,” proclaimed Dr. Cunningham as he exited the car and walked toward an opening in the wrought iron fence. Benjamin and Beth followed Dr. Cunningham through a small gate in the fence into what first appeared to be a playground. However, as Benjamin and Beth continued walking behind Dr. Cunningham, they noticed a series of grave markers set flush to the ground. They weren’t in a playground. They were in a cemetery. Dr. Cunningham stopped walking.

“There’s Noah Ellis,” as Dr. Cunningham pointed to a grave marker just off the main path.

“What do you mean, there’s Noah?” asked Benjamin in a confused voice.

“The young boy that you described you saw on the lake is buried in that grave. He drowned in Teller’s Cove three years ago trying to save his younger sister. I know because I was there to help pull his body out of the water. He saved his sister, but we couldn’t save him.”

“How can that be? It’s impossible. Benjamin talked to Noah and Noah gave him a fishing lure,” said Beth.

“I don’t know Beth. I don’t have an answer for you. Maybe it was just a boy that looked like Noah. I just don’t have an answer for you,” said Dr. Cunningham.

“Where is Noah’s family?” asked Beth.

“The family moved out of the area about two years ago. Too many bad memories. I don’t know where they moved to.”

As Benjamin listened to their conversation, he walked closer to the grave site and noticed there was a porcelain picture embedded in the gravestone. He bent down on one knee to see the picture in detail. The picture was of a smiling young boy with shaggy black hair and a facial discoloration from his left ear to the bottom of his jaw. It was definitely the young boy Benjamin saw at the lake. It was Noah. Something had happened that no one could explain.

“Can we go now, Dr. Cunningham. I need to go home and try to figure out how to pull all of this together,” asked Benjamin.

“Of course. I’m sure there is a reasonable explanation to all of this.”

They rode the ten minutes back to town talking back and forth offering ideas on how all of this could have happened. Nothing sounded possible or plausible, but it was good to at least talk it out. Once back at the clinic, Benjamin and Beth thanked Dr. Cunningham for his help and took their car and the frozen fish back home.

“I’m going to unpack the boat and put all the fishing gear into the boathouse. I won’t be needing it for a while. I’m going to take a fishing break. I’ll only be a few minutes,” said Benjamin.

“That’s fine. I’ll get lunch going and by the time you get done we’ll be able to relax and try to solve our mystery.”

As a warm breeze brushed across his back, Benjamin unloaded the boat and brought everything into the boathouse including the tacklebox where he stored all his lures. Benjamin put the tacklebox on the workbench just below the window in the boathouse. He lifted his head and looked through the window where he could see Lake Moultrie glistening under a rising mid-morning sun showing off its beauty and reminding Benjamin of all the good times he had had on Lake Moultrie fishing. It also reminded him of the happy young boy on the lake that no one could explain. Benjamin knew the memory of Noah would stay with him forever. As he turned and began to walk back to the house, he remembered he still had the tattered jig lure Noah had given him. It belonged in his tacklebox. He pulled the lure from his pocket and walked back to the tacklebox and opened the lid. It was there in the tacklebox that he saw something else he could not explain. Lying on top and in the middle of his other lures was his favorite blue and gray spinnerbait lure with the broken leader line still attached. This was the same lure he thought he had lost forever at the bottom of Lake Moultrie on the first day he saw Noah in Teller’s Cove. How did the lost lure get back into his tacklebox? Benjamin picked up the still damp lure. Under it was a small piece of paper. Only one letter was written on the paper. It was a capital “N.” It was from Noah. Benjamin could feel him nearby. He could only smile and stare at the blue and gray lure in disbelief, as tears welled up in his eyes and ran down his cheeks.

THE END

The Mystery of

the Dead-as-a-Doornail Author

By John RC Potter

Cornelia Vanstone took great pride in herself in general, but particularly for the following three reasons: her prize-winning gingersnap cookies, a trim waistline despite being in her mid-seventies, and her success as the author of several romance novels, known for their titillating titles and historical settings. Although she had never married, it was not for the lack of interest; Cornelia had many suitors and a few marriage proposals over the years. However, Cornelia had decided early on that her professional life as an author was more important than the personal, and she was grateful her parents had left their only child an admirable inheritance. Cornelia’s success as an author had been the icing on the cake, and she now had sufficient funds to travel often and live opulently. Her most recent novel-in-progress (she liked to think of them as novels, not as mere books) lay on the expansive antique desk in front of her. Cornelia pursed her mouth in a faint smile as she read the title on the cover of the manuscript: The Ripped Bodice! All of Cornelia’s titles ended with an exclamation mark (to the dismay of her publishers, but the author had insisted after the success of her first novel and thus the exclamation mark was present on each title ever since). Cornelia was brought out of her reverie by the imposing grandfather clock striking the hour in the hallway outside the living room: with the two bongs the anticipatory realization came to Cornelia that it was almost time for her first martini break of the afternoon. As she liked to say to friends, it was never too early for a martini! It was approximately 15 minutes before the hour, but the grandfather clock invariably lost time and Cornelia had given up on having it repaired again. As she carefully arranged her writing implements in front of her, Cornelia happened to look up at the gilded, ornate mirror that hung above her desk. It was just then in the reflection of the mirror that Cornelia saw the closed curtain on the French door move slightly, and with a sudden and inexplicable fear, she knew there was someone behind it.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………..

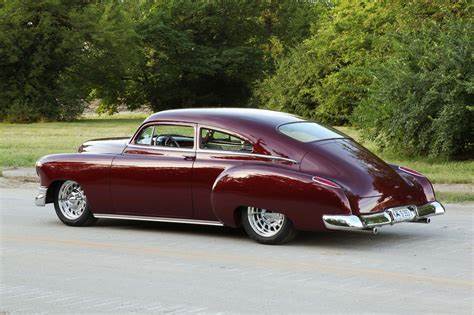

Alain Desvilles gave a heavy sigh as he manoeuvred his burgundy-coloured 1948 Buick Roadmaster along the winding road that led from Bayfield on Lake Huron to the town of Cornersville, to the northeast. He liked to think the car still had a very faint new-car odour about it despite being almost two years old. Alain had been the object of envy by many when he had purchased his Buick, which came with Dynaflow and its hydraulic transmission with torque converter. He was one of the few people in the area who owned a car that had an automatic manual transmission. For the most part, only well-heeled people could afford such cars. Alain did not

belong to that group of monied people, although after his parents had passed away during the war, he had been left with the family home and funds in the bank. No, Alain’s reason for purchasing an automatic transmission car was not a want, it was a need. Alain had been born with a condition medically known as ‘Amelia;’ he had no arms and could not have operated a standard transmission vehicle on the open roads. Thus, his Buick had been modified to allow Alain to drive with his feet; the controls to move the car into gear, and to accelerate and stop had been adapted to be operated from the steering wheel and not from the floor of the car. Truth be told, Alain rather prided himself on being a better driver with his two feet than most people were with their two hands. Due to his father’s attentive assistance, Alain learned to drive when young on the tractor and in his father’s pickup truck. Although those had been with standard transmission, the father and son had operated the vehicles in tandem and Alain had gained invaluable driving experience. It had been more than adequate and in fact, sufficient experience for him to later get his driving licence.

Again, he signed heavily, thinking there had to be a better way to make a living than taking photos of the odd crime scene and the occasional suspicious corpse. Alain then reminded himself how fortunate he was to have a job, considering he had no arms. He had been an only child born to a couple who were already nearing middle age when their son was born. Esther and Herbert Desvilles had been told they would never have children. It had seemed a miracle, then, when Esther discovered in her 40th year that she was pregnant. Her doctor had told Esther it was a risk for a woman of her age to have a child. Nonetheless, she and her husband vowed that it was worth taking the chance despite any possible negative outcome. As it turned out, Esther sailed through her pregnancy without issues arising and gave birth as if she had been doing it for years, with an ease reminiscent of their old and prodigious mother cat, Tinkerbell. Unfortunately, the baby was born deformed, without any arms. The nurse was crying when she placed the baby in Esther’s arms, and the doctor had a tear in his eye. Esther and Herbert decided then and there they had never seen a more perfect baby, and that the world would be his oyster. They knew their son would have to be a fighter and his journey through life would not be an easy one. However, the resolute couple vowed that their love, faith, and positivism would enable their son to have a decent, and hopefully fulfilling life.

Esther and Herbert never let Alain feel sorry for himself. When he was young sometimes other children made fun of Alain or stared at him and pointed. Occasionally it would make him cry or despondent but his parents always told him to believe in himself and reminded him about sticks and stones. Alain was brought out of his reverie, thinking back to his parents and the fact that he was now almost the same age as his mother when she gave birth to him when he steered his car around a gentle bend in the road and glanced at a diminutive, white-haired elderly woman who was tending her garden in a farmyard. It was Annie Withers, who had been a close friend of his mother all her life and up until her death. Alain took his left foot off the steering wheel and gave a gentle tap-tap on the horn, then gave his foot a brief wave out the window. The old woman waved back, then raised her hand to her forehead to shield her eyes from the direct, harsh June sunshine. In the rearview mirror, Alain could see Annie disappear from view as his car went over the crest of a hill. Seeing Annie brought back memories of Alain’s childhood. She had been his teacher in the one-room school on the concession road near his home, walking distance outside Bayfield. Like Alain’s mother, Annie had been one of his champions, who had always believed in him and made him believe in himself.

Out of what many would have thought was an insurmountable obstacle – born without arms – Alain had overcome the odds. He had gone to public school, then high school, and graduated with academic success. However, Alain had decided against attending university because he already knew that he wanted to work and earn money. Alain had two passions: one was taking photos and

the other was reading mysteries. He was so talented at picture-taking that when in his teens Alain had won awards in several competitions. His parents had installed a dark room in their home for their son. During high school due to taking photos for a variety of occasions, Alain was able to earn the funds he required to purchase mystery books for his steadily growing collection in the library he had created in the storeroom of his parent’s home. At times when he was low on funds, Alain would borrow mystery books from local libraries. When Alain finished high school, his parents assisted him in creating his photography office by converting the largely unused front parlour and having a door installed to the dark room that was beside it, a space that had previously been an oversized cloak closet.

When he was a child and began reading mysteries (at that time, Sherlock Holmes was a favourite, but he later became enamoured of Rex Stout, Ellery Queen, Raymond Chandler, Dorothy Sayers, Ngaio Marsh, and his all-time favourite, Agatha Christie), Alain imagined himself as a sleuth and later fancied himself becoming a detective. However, being realistic he knew that it would be nearly impossible to achieve that goal. It was more practical to follow his love of photography as a profession and to enjoy his mystery books and amateur sleuthing as a pastime. Nonetheless, Alain had gained the reputation for being a bit of a sleuth when he was young: for several years, the popular tri-county newspaper, The Huron Howler ran a mystery-solving competition in a special monthly issue and Alain had won a record 10 times. His photo had appeared in the paper for that distinction, and many of the newspaper’s readers were amazed that the winner had no arms. It later came to Alain’s ears that Bart Baxter, the curmudgeonly old foreman at the piano factory in Cornersville had quipped to his co-workers that Alain was “the armless armchair detective” and this joke had made its rounds for months in the community. Nonetheless, because he had a reputation for being adept at solving these newspaper mystery stories, Alain was considered a good problem solver with admirable deductive skills, and a top-notch photographer. That is how he ended up being hired to take pictures of crime scenes and the reason he was driving into Cornersville, now having reached the outskirts of the picturesque farming town.

Alain did not only take photos of crime scenes because otherwise, he would also not have much of an income; there were not that many crime scenes and murders in the tri-county area where his time and talent were occasionally required. Alain briefly took one foot off the steering wheel to scratch his nose and signed again. Why was he signing so much, Alain wondered. He should be excited at the prospect of taking photos of a crime scene, apparently a murder. Then it came to him: whenever he was in such a situation there were always people who may have heard of him but had never seen the armless photographer at work. They were always amazed and incredulous at how he was able to take such important photos. Moreover, and what further irked Alain, all too often strangers and new acquaintances mispronounced his name, and assumed he was from the province of Quebec or even France (which he was not) and that he spoke fluent French (which he did). One may as well be from Mars as from either Quebec or France, as far as many of the locals were concerned. Alain was considered a foreigner due to his French-sounding name and was viewed as askance due to his unique physical appearance as a result of being what many considered an armless wonder. Over the years he had been called Allen (for those who at least tried to pronounce his name correctly) or Al (for those who did not want to bother), or even Elaine (for those with a sense of warped and misplaced humour). As well, to add insult to injury, a few times he had been asked by thick-headed dumbbell if he was a Frog (a pejorative reference to anyone of French descent).

Bart at the piano factory had said that under his breath one day when Alain had been drinking his coffee at The Koffee Klatsch, the most popular bakery and coffee shop in Cornersville; it was run by the stolid and solid Helga Hartlieb (an emigre from Germany to the town in the late 30s, but

no one dared to make fun of her name or genealogy). Alain grinned at a memory of Helga and what she had said one day about him as he was leaving her establishment, as he had slipped off his loafer and adeptly turned the door handle with his upraised foot. Normally rather taciturn, the robust and busty Helga had stated in her still-heavily accented Germanic voice to a waitress who was lounging against the front counter, “Just think vat else he can do with them feets!” Alain was unsure whether or not Helga had intended for him to hear her rather ribald comment. He wondered if the woman was interested in him. It had happened before, as regards women who were curious about being with a man without arms. Alain had occasionally dated over the years but did not want to marry because of concern he would begat children born with his condition. His parents had said it was not, but in any case, Alain’s interest in women was minimal. Glancing in the rearview mirror, Alain had to admit that the face that looked back at him was no slouch in the looks department: a full head of wavy black hair, a pencil-thin moustache, sea-blue eyes set far apart, quite large ears, and what he liked to think was a Grecian nose. Other than the fact that he had no arms, Alain thought the only other drawback was his large head seemed rather out of proportion with his short stature.

It occurred to Alain as he slowed down near the first stop sign from that direction into the town of Cornersville that after his photo-taking at the crime scene, he could drop by the library on the main street and see if there were any new mystery novels on the shelves. He preferred the library in Cornersville over the one in Bayfield because it was such a beautiful old brick building and with an extensive range of books on all subjects, whilst the library in the village was smaller and with more limited offerings. Alain was brought out of his mystery book reverie when he came to the stoplights at the main intersection of the town, and then headed first east for a few blocks and then made a left turn that would take him to his destination: he was to take photographs at a crime scene on Mansfield Mews, otherwise referred to by locals as ‘Rich Man’s Row’ because it was where the most affluent Cornersvillians lived: the young white-collared professionals and old-monied families of the town. Alain’s Buick crept up the street until it arrived at the address he had been given: it was at 100 Mansfield Mews that he stopped his car completely and gave a low whistle when he saw the nameplate on one of the stone pillars at the edge of the drive. It proclaimed ‘Mansfield Manor’ and was the property of one of the town’s best-known residents, Cornelia Vanstone, a celebrated author of romance books.

Alain turned in the driveway and slowly drove to a parking place near the double garage. A police car was already there as well as a car he thought looked to be the coroner’s. Alain stopped the car, turning off the key with one bare foot and putting the car in the brake position with his other. Afterward, he flipped open the car door inside handle with his left foot and pushed the door open. He then plopped his bare feet down on the floor of the car and snuggled first one foot and then the other into his slip-on loafers. Alain quickly and adeptly hopped out of the car and then went to the rear door on the driver’s side; he again took his left foot out of the loafer and lifting it opened the back door, balancing on his right leg. From years of practice, he grabbed his leather camera bag with his foot and then bowing over slightly, he slipped the bag over his head. Standing upright again, Alain turned toward the impressive and stately house, admiring it. Like most people in small towns and the countryside, Alain had left the keys in the car and the door unlocked from habit and the knowledge that there was no need for concern. There may well be the occasional murder in the tri-county area, but thefts were few and far between!

Walking up the winding flagstone path that led to the front door, the camera bag jostling against his side, Alain’s ever active and always inquiring mind was thinking ahead to what had happened at the author’s gracious home. As he came to the front door it opened and there stood one of the men from the Cornersville Police Force, Homer Thuddly. He sometimes saw Homer at The

Koffee Klatsch and they had known each other from a few other cases in the past. “Hello Al,” Homer said in his deadpan and monotone voice. “The Chief Constable is waiting for you in the living room.” He stood aside and allowed Alain to come inside the wide and charming hallway, and then Homer opened the door and went into another room along the hall.

Alain made his way down the hall and then walked quietly and slowly into the elegant living room. Aside from the Chief Constable, Orville Hatsfield, there was another police officer in the room whom Alain did not recognise, and another man he knew to be the coroner from Exeter, who had responsibilities in the tri-county area and Alain had met previously. The Chief Constable turned toward Alain and nodded briefly, stating “Allen, this is a murder scene. In a few minutes, we will need you to take crime scene photos of the deceased. The Coroner, Roy Denton, is just finishing his examination of the body. Not sure if you know Jake Perkins, he is a new officer on our force here in Cornersville.”

From where he was standing just inside the arched doorway into the expansive living room, Alain could see the Coroner crouching down on the far side of an expensive floral chintz sofa. Although Alain could not see the body he knew the Coroner was examining it; he had not turned from his squatting position to acknowledge the photographer’s presence. Police Officer Perkins, however, turned from where he was standing near the Coroner and gave Alain a slight nod, with a wide-eyed look on his face. Alain assumed the Chief Constable had informed his new officer that the crime scene photographer had no arms, but his incredulous stare spoke volumes. Alain looked over at the Chief Constable. “I assume the deceased is the author, Cornelia Vanstone,” he stated.

“Yep,” Hatsfield replied.

“What was the manner of death,” Alain asked.

“Apparently strangulation,” the other man responded in a low voice. “But there is an odd touch to this murder, which you will see soon when you take the crime scene photos.”

“Any witnesses?” Alain asked. “Any clues?”

“Three witnesses,” the Chief Constable responded flatly. “They are waiting in the dining room with Homer. I know you are an armchair detective, Allen, but as for clues, I am not at liberty to say.”

“Three witnesses!” Alain blurted out, “That is very interesting. Talk about an embarrassment of riches...er, witnesses.” The Chief Constable smirked at Alain’s unexpected attempt at humour, then rolled his eyes.

It was at that point the Coroner stood up and turned towards the other men. He nodded toward Alain, whom he knew from a few previous crime scenes, including the most recent being the year before when Widow Wiggins in Brucefield had died rather suspiciously: she had been found amongst the tomato plants in her large and well-tended garden with a bloody wound at her temple. It was later determined that the widow had a heart attack whilst gardening and her head had struck a large rock as she fell. Ever since that work assignment, Alain had an aversion to eating tomatoes. “Well, I have finished my examination,” the Coroner said. “Mr. Desvilles can now take the crime scene photos.”

Alain moved with a steady stride toward the sofa, anticipating what the deceased author would look like in death. Police Officer Perkins continued to stare at Alain as if he had sprouted a second head, obviously wondering how an armless photographer could take any pictures, let alone those required for a crime scene. When Alain walked around the sofa he could not help but be